Oiling the Wheels of the Economy

The privatisation of state oil companies shows the desire to reform outdated economic models is genuine.

The fight between the London and New York stock exchanges to secure the listing of Saudi Arabia’s national oil company, Saudi Aramco, amplifies the significance of what Riyadh is attempting to do.

While some people question the $2 trillion valuation that has been suggested for Aramco, with more conservative estimates putting the firm’s worth between $1 trillion-$1.5 trillion, the flotation of up to 5 per cent of the world’s biggest oil company, planned for 2018, is set to be the largest listing in history.

“What makes this different from other listings is the size of the offering,” says Steven Drake, head of Middle East capital markets and accounting advisory services at the UK’s PwC. “The valuations being talked about would make it by far the largest IPO [initial public offering] ever, and likely ever to happen.”

Many vital details have yet to be announced, such as what parts of the huge Aramco business are actually being offered to investors, what percentage of the firm will be floated, how far Aramco will open its books, and what influence on policy and business decisions shareholders will have.

Bigger picture

As these details emerge over the coming months and as the battle between the world’s financial centres to host the Aramco listing intensifies, the IPO will generate headlines around the world for the rest of 2017 and 2018. But for those whose focus is closer to home, the importance of the flotation is more significant than delivering capital to Saudi Arabia.

For, while the IPO could generate as much as $100bn for the kingdom, the sale is merely the biggest piece of a structural reform agenda to install a private sector-led model for economic growth in place of the traditional state-led model, following the collapse in oil prices from June 2014 to today’s ‘new normal’ levels of about $50 a barrel.

In July, Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Energy, Industry & Mineral Resources Khalid al-Falih, who is also chairman of Aramco, said the oil giant’s share sale is the “most notable feature of the kingdom’s transformation”, and forms a central pillar of the Vision 2030 reform programme.

And Saudi Arabia is not the only country seeking to restructure its national energy assets to boost economic reforms. In the UAE, the world’s fourth-biggest oil producer, Abu Dhabi is also embarking upon the partial privatisation of its oil industry through share sales in the fuel distribution businesses of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc). Oman and Kuwait are also assessing the flotation of parts of their oil firms.

The privatisation of the Gulf’s politically and economically most important entities, which have for decades been the engines of regional growth and vital state assets for underpinning national stability and exerting international influence, ushers in a new era for governments and business relationships in the GCC and beyond.

Capital requirements

While the need to diversify the Saudi economy has long been acknowledged, with oil sales accounting for 44.3 per cent of GDP and 62 per cent of budget revenues, the slump in oil prices since 2014 has expedited the process. The dramatic fall in prices, from $115 a barrel in June 2014 to under $30 in January 2016, led to the IMF warning that Saudi Arabia could run out of vital financial reserves in as little as five years unless major reforms were introduced. Riyadh heeded the IMF’s advice and in April 2016 launched its Vision 2030 reform agenda. This was quickly followed up with the 2020 National Transformation Programme, the delivery plan.

Vision 2030 aims to increase the role of the private sector in Saudi Arabia, streamline government spending by reducing subsidies, and drive job creation for local people.

“The transformation of the economy and Vision 2030 will need a lot of funds and resources, and the privatisation programme will be central for this,” says Monica Malik, chief economist at Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank. “Saudi Arabia is looking to create a large sovereign wealth fund to support domestic growth and diversification, but also for external investments into various sectors to make them less reliant on oil.”

Although Riyadh is also raising finance by borrowing on the domestic and international debt markets, including raising $17.5bn from the biggest-ever bond sale by an emerging market nation in October last year, the drop in foreign reserves to below $500bn in April this year, from $730bn in 2014, highlights the urgency of raising capital to repair public finances and support spending. The decision to offer 5 per cent of its largest company to the market provides a way of doing this, while retaining control over its largest economic asset.

“Riyadh realises it can raise a significant amount of cash from a relatively small percentage selldown,” says PwC’s Drake. “They can raise a decent amount of capital that can be recycled within the economy or reinvested overseas without changing ownership; the government still retains control.”

While the quest for capital sits at the core of the decision to sell shares in Aramco, privatising Riyadh’s most prized asset sends a clear message from King Salman and his son, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, that things must change.

“The Aramco IPO shows determination for reform, and sends a signal, particularly to those resisting internally, that change is necessary,” says Robin Mills, CEO of UAE-based Qamar Energy. “And with [Prince] Mohammed bin Salman, who is driving the IPO, having been recently named crown prince, it is important to his standing within the kingdom politically.”

According to Mills, opening up the oil producer to the public will also boost transparency and improve the competitiveness of the country’s economic foundations. “It will make [Aramco] competitive and more commercially minded, which will create more value,” he says.

International Expansion

Moreover, increased transparency and the privatisation of oil assets should grow the prospects for further foreign ventures, with energy minister Al-Falih regularly saying the listing will assist Aramco’s goal of forging global partnerships and increasing its overseas portfolio.

“Officials have indicated Aramco would be an international industrial conglomerate, and I think the IPO is part of this,” says Malik. “A lot of GCC states are looking to form new partnerships and refining tie-ups with countries in Asia in particular. Kuwait has done that with tie-ups in Vietnam and GCC producers are looking to China and other energy importers.”

According to Mills, this is also the case for Abu Dhabi, which has several non-core assets it can potentially sell to the public. “Adnoc is seeking to boost international partnerships and relationships, and bring in other partners for future opportunities,” he says.

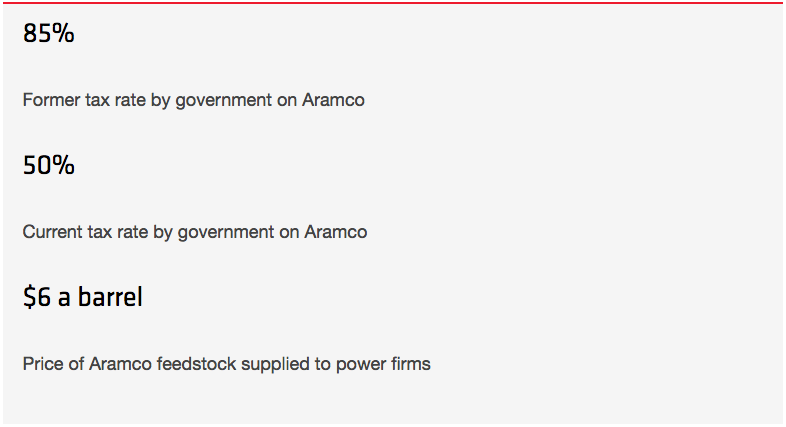

While Riyadh has made moves to increase the attractiveness of the IPO, such as the announcement in March that it would cut the government’s tax rate on Aramco from 85 to 50 per cent, several challenges remain to attracting investors and succeeding with the planned transaction.

In addition to lower oil prices, the kingdom’s high energy subsidies will make some potential investors wary of its ability to deliver maximum returns. About one third of Aramco’s output is sold for domestic purposes at a heavily discounted rate, with power generation companies receiving feedstock at rates of less than $6 a barrel.

While Riyadh has committed to cutting domestic fuel subsidies, it is a politically sensitive issue, with citizens also facing a hike in power tariffs in tandem with higher gasoline prices as part of the reform programme. However, success in subsidy removal is vital if Aramco is to achieve its targeted valuation.

“Subsidies may be an issue for the privatisation plans, especially on the distribution part of the business,” says Malik. “A plus point for Abu Dhabi is that fuel prices are already liberalised and are set on a monthly basis. Saudi Arabia is still at the early stages of its subsidy reform programme.”

Political interference is also a concern for some potential investors, particularly with only a minority stake on offer. Due to Aramco’s importance to the economy, decisions on production and capacity will remain firmly in control of the government after the IPO.

One regional banker says state sovereignty over major decisions may provide a stumbling block to the oil firm achieving maximum value from its IPO. “A lot of large fund managers have said if they want to get an oil play, there are other ways to do it, and they wouldn’t do one for such a small part of a firm where ultimately the decision-making will be done for the benefit of the country,” says the banker.

Saudi Arabia’s decision to sell part of its most prized asset is understandable. Up to $100bn of investment would boost its sovereign wealth funds and enable it to make real progress with diversification and economic reforms. Whether Riyadh can benefit as much as it hopes depends on its ability to juggle the concerns of foreign investors with the needs of its people.