Saudi railway privatisation faces mounting challenges

Analysts differ in their opinions on whether the kingdom’s plan to privatise its rail network and use PPPs to build new lines will succeed

It takes about four hours and twenty minutes, and at least $16, for the passenger trains owned and operated by Saudi Railways Organisation (SRO) to negotiate the 449-kilometre Riyadh-Dammam route, which passes through Al-Ahsa and Abqaiq.

The long journey time is not the only factor causing passengers to prefer to take a plane or drive a car between the capital and the eastern city instead.

Several incidents in recent years indicate an upgrade of the network and trains are long overdue. Flooding from heavy rains in February caused the rail line near Dammam to drift, resulting in one train going off course and injuring 18 of the train’s 193 passengers. In 2012, stolen optical fibre cables were blamed for causing a disruption to the train network’s communication and control systems that derailed a train carrying more than 300 passengers. The more regular incidents, however, involve collisions with camels crossing the tracks.

Reviving a railway

It is understood there has been hardly any additional investment made in the railway since its completion in 1951. Despite, or because of, the relatively poor state of the line, the kingdom’s Public Transport Authority (PTA) has included it, along with the more modern North-South Railway and potentially other planned long-distance rail schemes, in its privatisation programme for which interest from rail developers, operators, consultants and investors is currently being sought.

The privatisation plan appears to have an open timeline and does not prescribe specific investment models for the various assets under consideration, which include track, systems and telecoms, rolling stock, and the operation and maintenance of the railways.

“I think the objective of the EoI [expression of interest] is to assess general interest in assets and establish market appetite for different investment models,” the head of one firm planning to show interest in the project tells MEED.

Risky business

The risks for companies participating in Saudi Arabia’s rail privatisation programme, both for new and existing infrastructure, are many. They range from the lack of a regulatory framework to the complexity of building and operating a rail network and competition from other forms of transport such as air travel and cars.

“In practice, private sector involvement in the railways will be a new thing for the country and will have to break new ground on a wide variety of things,” says Richard Kupisz, CEO of Maxwell Stamp Saudi Arabia. He says the novelty of the method need not be a deal breaker. “Most of the big utility privatisations around the world were similarly groundbreaking …. The regulatory framework was established as part of the privatisation programme,” says Kupisz.

The crucial issue for the government is to ensure the privatisation and public-private partnership (PPP) structures enable the private operator to earn a reasonable return at an acceptable level of risk, he adds.

Kupisz also underscores the special need to adopt a risk structure that will satisfy lenders who are generally more conservative than equity investors, especially for the capital-intensive parts of the project, such as the track and rolling stock.

It appears the PTA and its adviser, US-based AT Kearney, are planning to do just that. The potential privatisation scope being offered has been split into two. The first covers infrastructure, which includes tracks, intermodal assets such as freight yards and passenger stations, and workshops or depots. The second covers operations, which include the purchase and operations of new and existing rolling stock.

It also appears, from an operating revenue perspective, that the newer 2,750km North-South Railway, currently owned by the Public Investment Fund through Saudi Railway Company (SAR), could be more promising to potential investors.

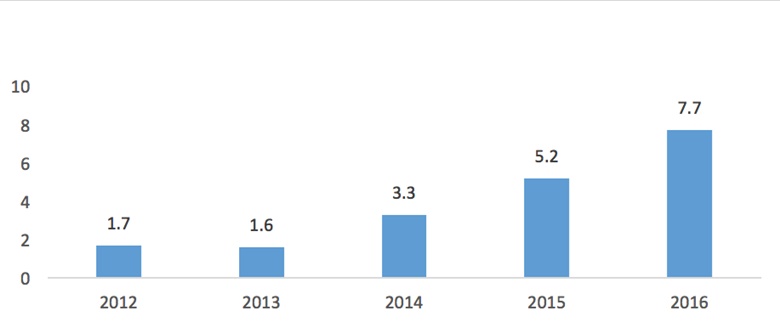

North-South railway total freight – million tonnes

The railway carried 7.7 million tonnes of freight in 2016, up from 1.7 million tonnes when it started operating in 2012, an annual average increase equivalent to 45.9 per cent. The business case for the passenger component of the rail line is less strong, given it only started operating this year.

However, this is expected to improve, especially if it is able to be shown that the railway is a more cost-effective, safer or efficient alternative to flying or driving. The line’s six passenger stations could also potentially accommodate retail schemes to supplement revenue generated from ticket sales.

Similarly, the Riyadh-Dammam cargo line and the Riyadh dry port could offer investment opportunities. The railway carried 671,000 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs) of container freight in 2016, while the dry port handled about 700,000 TEUs.

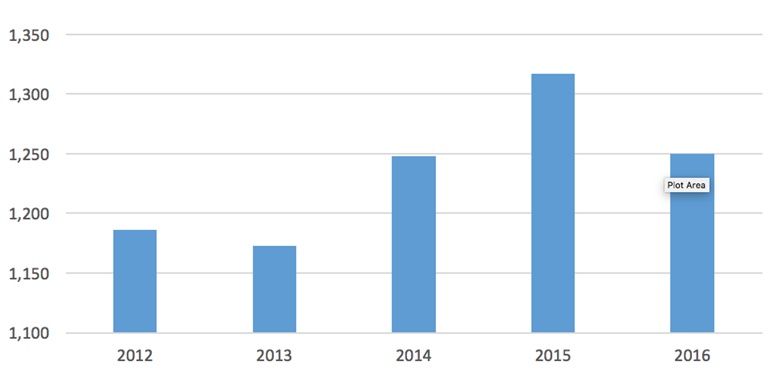

Riyadh Dammam passenger traffic – thousand passengers

The case for the Riyadh-Dammam passenger line, which generates roughly $25m-$30m in ticket sales annually, is less convincing, given the slow growth in passenger numbers. The railway carried 1.19 million passengers in 2012, which increased to 1.32 million in 2015, before retreating back to 1.25 million in 2016.

Rare success

A consultant with a multinational company has expressed strong reservations about privatising Saudi Arabia’s existing railways and using a PPP structure to build new ones, including the planned Landbridge and urban rail systems proposed for Mecca, Jeddah, Medina and Dammam.

“The likelihood of failing is significantly high,” the consultant tells MEED. He says that apart from private mining railways, using a PPP structure for building and operating a railway has hardly worked anywhere in the world. “Rail infrastructure is simply not designed to pay for itself or to generate income for stakeholders unless the scheme incorporates a commercial real estate component,” he adds.

The consultant says the complexity of a rail network and the lack of a sufficient regulatory framework as well as the exceptionally long payback period for investors do not bode well for the kingdom’s railway projects. “I would not expect international financial institutions to be keen in participating [in the programme],” he tells MEED.

Despite the pessimism and risks, many others agree the PTA is heading in the right direction by adopting an open timeline and fostering a close consultation process with all market players in approaching the privatisation of its mainline railways. “They are testing market interest before even undertaking an asset valuation exercise to ensure they are not trying to sell something the market will not buy,” a source tells MEED.